Before AI Can Accelerate Science, We Have to Fix Science

Or, science’s tollbooth problem

Welcome to The Third Hemisphere, where I try to make sense of how AI is reshaping work, thinking, and creativity, often by watching my own assumptions get upended. If you were forwarded this and want to subscribe, click below. If you want to support a real human writing about AI, upgrade to paid.

Where is all the AI-driven scientific progress?

Over the holidays a friend texted me a recent Hard Fork episode: “Where Is All the AI-Driven Scientific Progress?” The episode features Sam Rodriques, whose company Edison Scientific just launched an “AI scientist” called Kosmos that he claims can accomplish six months of PhD-level research in a single overnight run for a few hundred dollars. The tool reads 1,500 papers, writes 42,000 lines of code, and, so the pitch goes, surfaces insights that match what human scientists would have found.

The episode sounds weirdly like sponsored content for Edison Scientific, but it also crystallizes something important. AI leaders have been promising that AI will cure cancer, double the human lifespan, compress a century of scientific progress into a decade. This rhetoric has been a central justification for massive AI investment, or at least a central pillar of AI hype. While people have criticized these claims since day 1, the fact that The New York Times is now asking “where is all the progress?” suggests that a much wider audience is receptive to skepticism.

Personally, I think it’s too soon to evaluate AI’s full impact on science. It’s certainly not all hype: I’m at a biomedical research institution and I see plenty of evidence that AI tools are helping individual scientists and doctors speed up or improve their work. But helping individuals work better and faster isn’t the same as accelerating scientific progress because of the kind of work scientists are incentivized to do. Just as I was about to hit publish on this post, I saw a study published yesterday in Nature that confirms this paradox: scientists who adopt AI publish three times more papers and receive nearly five times more citations (great for scientists). Yet the same study found that AI adoption shrinks the collective range of scientific topics by nearly 5 percent (bad for science). AI tools, the authors conclude, “seem to automate established fields rather than explore new ones.”

The upshot is that AI, even in the best case scenarios, will have a limited effect on scientific progress unless we also reform how science gets done. A corollary to that is not to let flashy promises of an AI-driven scientific revolution distract from making more urgent, commonsense reforms to science.

The production-progress paradox

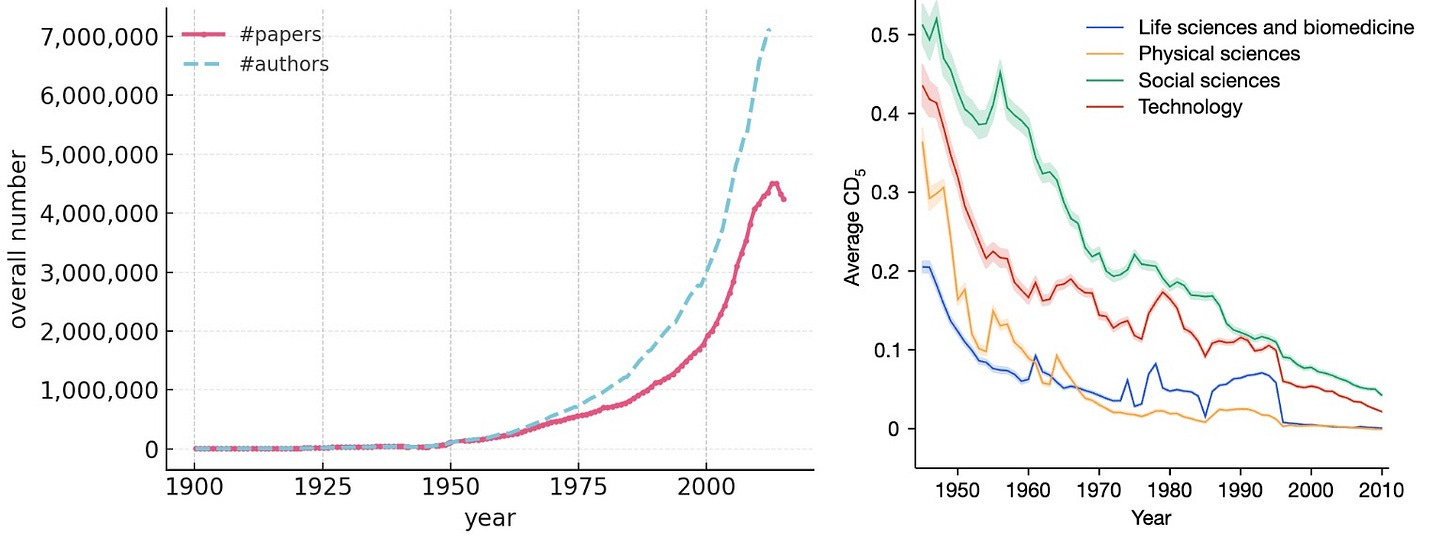

There’s an article I read this summer that I can’t stop thinking about. Computer scientists Arvind Narayanan and Sayash Kapoor detail what they call the “production-progress paradox.” Scientific publication has grown exponentially (500-fold between 1900 and 2015). The scientific workforce has also greatly expanded. And, despite the gripes of scientists, funding has remained enviably robust (just ask any artist). But actual progress, by available measures, has been flat or declining. More papers, more researchers, ample funding. Fewer breakthroughs:

Why the paradox? Narayanan and Kapoor suggest the problem isn’t lack of technology but “the way we’ve structured the practice of science, and so the efficiency of converting scientific inputs into progress is dropping.” Start with the incentives. At most research universities, scientists are responsible for raising their own funds through grants. When success rates are 10 percent, that creates enormous pressure to keep producing, to always have the next grant application in the pipeline, the next paper ready to publish. Institutions reinforce this by judging researchers on what’s easy to measure: publication counts, grant dollars, citation metrics. Progress is hard to quantify on the timescales of tenure reviews; production isn’t.

The rational response from scientists is risk aversion. Academic scientist positions are competitive, and if you want to keep yours, you have one chance to show your research program is worthwhile when tenure review comes up 5 to 7 years later. You can’t afford to spend those critical years chasing uncertain or high-risk ideas. Under these pressures, it’s inevitable that scientists will tend to pursue safe, incremental projects—work that will reliably yield papers and win grants, even if it never significantly advances science.

Scale that up across the scientific enterprise and you get overproduction: a flood of papers, many of them important, to be sure, but not many that are truly groundbreaking. This overproduction, according to Narayanan and Kapoor, creates perverse second-order effects. Scientists can only read so many papers a year. When the volume explodes, novel ideas get buried in the noise. Attention flows to already-established work, the papers people already know to look for. This dynamic creates a feedback loop. Because attention is scarce and flows to established work, it becomes even riskier to depart from the canon. So researchers play it safer. Which produces more incremental papers. Which makes attention scarcer. And so on.

Now sprinkle in something like generative AI. If it only accelerates markers of scientific production without touching the underlying incentives, science will get more papers, faster—but within the same broken reward structure, the same attention scarcity, the same pressure toward safe, incremental work. Early evidence suggests this is exactly what’s happening. A recent study in Science analyzed over two million preprints and found that LLM adoption is associated with posting 36 to 60 percent more manuscripts.1 But for LLM-assisted manuscripts, writing complexity correlated with lower publication probability, the opposite of what’s historically been true. One interpretation is people are churning out lower-quality work dressed up in fancy prose. Meanwhile, a study of major AI conferences found that up to 17 percent of peer reviews show signs of substantial LLM modification; in one eye-grabbing statistic, the use of the the word “meticulous” appeared more than 34 times as often in reviews after ChatGPT came out than in the previous year. So we have: AI helping scientists write papers of questionable depth, which AI then reviews with questionable rigor. The metrics of production tick upward, while progress stalls.

Narayanan and Kapoor’s diagnosis is blunt: AI companies, science funders, and policymakers “seem oblivious to what the actual bottlenecks to scientific progress are. They are simply trying to accelerate production, which is like adding lanes to a highway when the slowdown is actually caused by a tollbooth.”

A system for dispensing chicken feed

So if Narayanan and Kapoor are right that the problem is at the tollbooth, not the number of lanes in the highway, the question becomes: why is the system built this way? And what would it take to actually change it?

A recent interview with Mike Lauer of the NIH offers a rare candid view into the most pressing obstacles slowing science, at least when it comes to biomedical research. Lauer spent years as Deputy Director for Extramural Research at the NIH, which means he oversaw the NIH’s $32 billion budget in external grants—the largest funder of biomedical research in the world. Nearly everything about academic biomedical research is shaped by the NIH grant-making system, which Lauer calls “fundamentally broken” and in some cases, an “unmitigated disaster.”

These are verbal grenades, by academic standards. By “broken,” Lauer doesn’t mean corrupt. He means that the system has become so hyper-competitive and inefficient that it is “dangerous and corrosive” to scientific progress.

It’s worth diving into why this system exists the way it does, simply to illustrate how historically contingent it is. Before World War II, the government barely funded science and scientists wanted it that way. But the war changed everything—yes, the Manhattan Project, but also the mass production of penicillin—and afterward, the government decided to keep funding research. The question was how.

The NIH grants program didn’t start with an act of Congress. In fact, in the 1940s, the NIH barely existed at all. It was just a small laboratory that had some leftover money after the price of penicillin dropped. The person who had Lauer’s job sent a letter to university deans: “If you have any need for some extra money, please let me know.” The response was overwhelming. By 1946, the program was running de facto. Congress made it legal later.

The model that emerged—small, time-limited, project-specific grants—wasn’t chosen through careful policy design. It was borrowed from the Rockefeller Foundation, which had adopted it during the Depression to limit the financial risk of doling out big grants to institutions. When the NIH decided to adopt the Rockefeller funding model, even the foundation’s medical science director warned against it, as a system of small grants would create a huge amount of administrative work and turn the government into “a dispensary of chicken feed.”

He was ignored, but he was right. Today, scientists spend approximately 45 percent of their research-related time on administrative requirements rather than doing science. Grant applications have ballooned from 4 pages in the 1950s to 100-150 pages today (Lauer says he’s seen grants top out at 1,000 pages). Despite all this grunt work, success rates have plummeted from 60 percent in the 1950s to around 10 percent today. The average age at which a scientist receives their first major independent grant is now 45.

A quick comparison shows how bizarre this is. Neurosurgery is one of the most demanding careers a person can choose—years of grueling training, life-or-death stakes. Yet neurosurgeons are performing independent brain surgery by their mid-thirties at the latest. A scientist, meanwhile, can’t run their own lab until 45. What sense of proportion is that? Someone can be trusted to cut into a human brain a full decade before they’re considered ready to design experiments on their own. That’s half a person’s working career, it’s absurd, and there’s no reason for it other than the inertia of a flawed bureaucratic system with perverse incentives.

Where is all the scientific progress driven by… sensible bureaucratic reform?

AI is being positioned as a savior for science. The timing feels almost providential: just as the White House seems hellbent on cutting federal research funding, AI arrives to pick up the slack. And the narrative is convenient for AI companies too. The promise of curing cancer and doubling lifespans helps justify massive investment and favorable policy treatment.

But if Narayanan, Kapoor, and Lauer are right, which I think they are, science won’t be able to fully take advantage of any benefits of AI until it undergoes major institutional reform.

Lauer’s prescription is wonky: block grants—large, flexible funding to institutions rather than small, rigid grants to individual projects. Fewer “bureaucratic units,” less time on paperwork, more room for risk-taking. He points to the NIH’s own intramural program as proof of concept. Barney Graham, who helped develop the COVID and RSV vaccines, told Lauer he “absolutely” could not have done that work in the extramural system. Whether Lauer’s specific prescription is right, I can’t say. Block grants would introduce their own problems like institutional politics, uneven distribution, new forms of gatekeeping.

Regardless of what you think of block grants, Lauer’s broader point stands: a major bottleneck to scientific progress is organizational, not technological. Most scientists no longer work under conditions where they have the freedom to take risks without worrying whether their labs will be funded the next year.2 The reason scientists spend half their time on paperwork isn’t that they lack AI tools. The system is structured to reward production over progress, incremental research over risk-taking, volume over insight. No amount of AI can fix that.

I have nothing against Sam Rodriques, and I’m sure his AI co-scientist product Kosmos will help at the margins. But let’s not confuse tools like Kosmos for the solution to science’s problems. People like Mike Lauer, who spent years inside the NIH, are telling us that progress isn’t being held back by a lack of technology but by bureaucratic dysfunction. This is consistent with my experience in academia for years. If we want to cure cancer faster, the best thing to do is reform the institutions of biomedical research, not make a major bet on an uncertain technology to do it for us.

I’ll admit this makes for a way less engaging episode of Hard Fork, but at least “Where is all the scientific progress driven by sensible bureaucratic reform?” is the right question to ask.

For the uninitiated, preprints are drafts of scientific papers that get posted publicly before they undergo the peer review process at a scientific journal. So, anyone can publish a preprint, but a published paper in a journal is vetted by editors and peers. Many preprints are posted but never published. The authors interpret the probability that a preprint is accepted for publication as a proxy for quality. One might debate the validity of this interpretation for any given paper, but for a coarse, bird’s-eye view of the literature, it’s a reasonable guess.

Some may argue private funding is the answer. Personally, although I think the private sector has an important role in science, I’m skeptical that commercial entities would be willing to underwrite basic science, given its uneven returns on investment. Private philanthropy could also play a role, though it’s worth noting that a private foundation’s flawed model is exactly what the NIH adopted in the first place. The NIH has been an extraordinarily successful institution, by any metric; although in the political aftermath of the pandemic, many seem eager to burn it to the ground, but fixing it strikes me to be the best way forward.

I had a similar conversation with a friend yesterday, about how infuriatingly boring and incremental much of science has become - people ask the safe questions, instead of the fun risky ones. I 100% agree that the system is very, very broken, and I like the analysis you present here.

but - I think I have some counter examples. there are countries in Europe where the funding system is different; people don't have to continuously compete for small grants like in the US. yet, it seems that at least in some cases, because of the "comfortable" situation and the lack of competition, people... stop trying, and still largely pursue the easy, comfortable, incremental questions. now, admittedly, this is mostly an outsider observation, the academic system I'm by far the most familiar with is the UK one, which is similar to the US.

if this observation is correct (which it might not be), then removing the tollbooth alone might not do much. but maybe there's some kind of middle ground?

Insightful thanks. How best to fund risky research?